Financial Times February 3 2003.

Shuttle loss raises doubts on manned space flight

INQUIRIES LAUNCHED AFTER COLUMBIA CRASH KILLS SEVEN ASTRONAUTS

The astronauts' names on an insignia, which is part of the debris in Texas believed to be from the Columbia AP

By Clive Cookson, Victoria Griffith, Andrew Jack and Edward Alden

The loss of the shuttle Columbia has thrown the future of manned space flight into question as the world, waits

to discover whether the US will scale back its efforts or renew its commitment to space exploration.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration yesterday said Harold W. Gehman, a retired admiral who was also the lead

investigator into the 2000 attack on the USS Cole, would head the inquiry into Saturday's disaster in the skies above Texas,

which killed six US astronauts and an Israeli.

Mr Gehman was despatched to Shreveport, Louisiana, to begin the investigation.

Sean O'Keefe, Nasa administrator, said as well as Mr Gehman's independent team, the agency had established an internal

group to gather evidence, including securing debris from the shuttle that was spread across several southern states.

Mr O'Keefe refused to be drawn on causes of the crash during television interviews. "There is just no indication at this

juncture of any predominant theory," he said on ABC.

Speculation has focused on insulating foam that came off an external fuel tank during Columbia's launch and hit a wing,

as a possible cause of the accident.

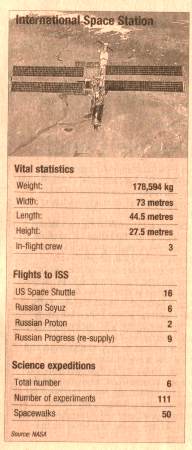

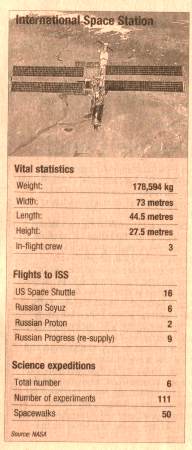

With the remaining three shuttles now grounded, a key supplier to Russia's space programme offered to step in to maintain

deliveries to the International Space Station, where three astronauts are on board.

Valery Ryumin, deputy-general constructor at the Energiya construction group, said Russia could take on responsibility

for future deliveries with its Proton rockets if it received additional funding.

The Russian space agency believes it can make up for the absence of shuttle flights to the ISS if the US overrides political

and legal obstacles to greater co-operation with Moscow.

The move would mark an important symbolic boost in co-operation between the two countries at a time of growing friendship

with Washington in the wake of Moscow's participation in the international coalition against terrorism since 2001.

Saturday's accident presents the first serious test of the decision by Nasa in the mid-1990s in effect to privatise

space shuttle operations by handing, over day-to-day management to Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

The aerospace companies established a joint venture - United Space Alliance - under a contract worth some $12bn over 10 years.

The first political reaction to the accident suggested President Bush will have widespread support if he decides to expand

the manned space programme and start serious development of a safer successor to the shuttle.

"We can't step back," Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas told Fox television. "We wouldn't be the greatest country on earth

if we did. This is the time to say we are not going to continue cutting [Nasa's] budget."

Senator Bill Nelson of Florida, a former astronaut, agreed: "We've got to fulfil our destiny as a character of people

as explorers and adventurers and go to Mars."

Financial Times February 3 2003.

Shuttle loss raises doubts on manned space flight

REACTION IN WASHINGTON SINCE THE CHALLENGER CATASTROPHE IN 1986,

RENEWED ENTHUSIASM FOR LAUNCHES HAS BEEN DRIVEN BY MILITARY NEEDS

Defiant US leaders vow to press ahead into space

By Edward Alden in Washington and Sheila McNulty in Houston

US political leaders vowed yesterday to push ahead with an ambitious space exploration programme even as the country

mourned the loss of the seven astronauts in the space shuttle Columbia.

The defiant reaction was in sharp contrast to 17 years ago, when the explosion of the Challenger halted all shuttle

launches for nearly three years, and led to a long period of recrimination and doubt about the future of the US space programme.

But with the country in a defiant mood on the eve of a likely war with Iraq, there has been little such uncertainty

this time as Americans marked the tragedy in their own ways.

Senator Joseph Lieberman, the leading candidate to challenge Mr Bush in the 2004 presidential election, said:

"We will not retreat from space, because we cannot know what wondrous discoveries await us if we abandon its exploration."

The catastrophic 1986 Challenger explosion, which took place before a vast audience of US schoolchildren watching

the first teacher being launched into space, shook the nation's confidence in space flight. It triggered several years

of debate on whether the missions were necessary, and encouraged the country to develop new satellite launch capabilities

as an alternative to shuttle flights.

But the mood of the US has changed greatly since the Challenger disaster. The September 11 attacks have rekindled the mixture

of fear and assertiveness that characterised the country in the early years of the cold war, the heyday of the US space

programme.

A sombre President George W. Bush, who cut short his weekend at Camp David to speak to the nation from the White House,

underscored that determination on Saturday. "The cause in which they died will continue," he said. "Mankind is led into

the darkness beyond our world by the inspiration of discovery and the longing to understand. Our journey into space will go on."

In Mr Bush's home state of Texas, people placed balloons, flowers and crosses in memory of the astronauts on patches of

the Columbia's debris that were scattered for 10 miles across the countryside. At mission control in the Johnson Space Centre,

Houston, a steady stream of visitors paid their respects with flags and wreaths.

But while the rhetoric of the shuttle missions has heroic and scientific, the rationale is largely military. As in

the 1950s and 1960s, when the programme was driven by a desire to remain ahead of the Soviet Union, the renewed

enthusiasm for space is also driven by military needs. The precision-guided weaponry and battlefield management

capabilities that have made the US the only global superpower depend on continued dominance in space.

Any recriminations out of Washington will probably be aimed at funding for the space programme, which many critics say

is inadequate despite burgeoning budget deficits. Congress will shortly begin considering the president's 2004 budget

proposals, which will be released today.

A report published in August 2000 from the General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, warned that

a one-third decline in the budget for the shuttle programme between 1995 and 2000 had raised safety concerns.

INVESTIGATION

Queries about rest of shuttle fleet

By Victoria Griffith in Boston

A specially appointed board will meet today in Louisiana to begin its investigation into the Columbia tragedy.

The "Space Shuttle Mishap Interagency Investigation Board", headed by a retired US admiral, will not only lay blame,

it will also alert the government to any defects that might keep the remaining three space shuttles from flying.

Early inquiries focused on a piece of insulation that fell from the shuttle's external fuel tank one minute after lift-off.

The foam hit the aircraft's left wing. Nasa was immediately concerned that the impact might have damaged the tiles that

protect the shuttle from high temperatures, but concluded damage had been minor. Yet when the Columbia began

re-entry, the space agency failed to pick up signals from the left wing.

As external temperatures reached 3,000°F, one theory goes, other tiles probably stripped off and metal began to melt.

The shuttle, unable to resist the heat, blew up.

The explosion raises grave questions about the health of the rest of the ageing Shuttle fleet. The Columbia, built in 1981,

had been updated just four years ago. Yet over the last two years, critics increasingly raised alarms about deterioration

in the fleet.

Last April, Richard Blomberg, former chair of the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, an independent group formed to review Nasa,

told a House of Representatives subcommittee he was concerned for space shuttle safety.

Nasa has had its share of tragedies, stemming from both equipment and human failure. In 1986, the Challenger space shuttle blew

up a minute after launch. This was attributed to low temperatures that prevented the rubber sealing joints in the

craft's solid fuel rocket booster from expanding.

Budget cuts in recent years have caused the space agency to lose craft with frightening frequency. In 1999, Nasa lost

two Mars bound spacecraft. The Polar Lander probably crashed on the Red Planet because of signalling problem in the

landing legs. The Climate Orbiter was lost as a human error failed to convert a calculation from English to metric measurements.

Regardless of the conclusions of the investigation, Nasa may find it harder to recover from this tragedy than from the

Challenger 17 years ago. Then, the US space agency had enough meat in its budget to store spare parts, allowing a replacement,

the Endeavour, to be built quickly.

Sean O'Keefe, Nasa head, warned that it was still far too early to say what went wrong with the Columbia reentry. The agency

appealed to the public yesterday to turn in any debris collected when pieces of the shuttle fell to the ground.

In the wake of past tragedies, investigations have always turned up surprising consensus on the cause. Yet finding out what

went wrong is only part of the challenge to be met in getting the space shuttle fleet in orbit once more. Nasa's budgetary

preview, which had been set for today, has been indefinitely postposed. The future safety of space missions will depend

a great deal on the amount of money allocated to the agency.

PRIVATE-SECTOR INVOLVEMENT

'Privatisation' under scrutiny

By Caroline Daniel in Chicago and Mark Odell in London

The Columbia accident presents the first serious test of the decision by Nasa in the mid-1990s in effect to privatise

the space shuttle operations by handing over the day-to-day management to Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

United Space Alliance (USA) was set up as a 50-50 joint venture by the two aerospace and defence companies in 1996 under

a contract worth some $12bn (E11.1bn) over 10 years.

Although Nasa retains prime responsibility for safety and overall management of the shuttle programme, the role

of USA will come under intense scrutiny, if, as suspected, the accident was caused by a mechanical or structural

failure on board Columbia.

The Nasa contract that established USA's responsibilities is performance-based and is "specifically written to meet

Nasa's primary goals of maintaining mission safety", according to USA's website.

Eighty per cent of the incentive fees under the contract are tied directly to safety performance.

But analysts were still unsure what if any liability issues USA might face after this latest accident.

"What is different with Challenger is they didn't have a private contracting team with responsibility, as they do now.

However, I would be surprised if there were any kind of liability issues here, because Nasa still manages the programme

and has a great deal of involvement," said Marco Caceres, space analyst at the Teal Group.

USA is responsible for almost every aspect of the shuttle's flight and ground programmes, ranging from mission planning and

flight operations to launch and recovery of the vehicle.

Boeing, Nasa's leading contractor, has a dual role in the shuttle programme - it is also the designated manufacturer

of the vehicles through its 1996 acquisition of Rockwell International.

The company, which derives about $2bn or 4 per cent of its annual revenues from its Nasa programmes, is already under

pressure from the continued slump in its main commercial aircraft business, making it more dependent on its defence

and space divisions.

But analysts think it unlikely that any hiatus in the shuttle programme would have much impact on Boeing or

Lockheed Martin, which does not state the value of its Nasa contracts but derives about 30 per cent of its revenues

from its space business.

Nevertheless, psychologically the shuttle accident could not have come at a worse time for either company's space businesses.

The commercial satellite business is in the depths of a severe recession, with new orders having all but dried up.

Mr Caceres believes the crash could prompt Nasa to speed efforts to upgrade the remaining three shuttles in the fleet,

as part of a $1.6bn programme. The spacecraft are essential to the continuation of the International Space Station project.

Once the shuttle upgrades are completed, Nasa could then decide whether it can rely on the existing fleet for 15 more years

or proceed with a follow-on vehicle. Any new spacecraft is still a decade away from reality, however.

"It would be a national embarrassment for Nasa to cancel the space shuttle and space station programmes. But what they

could do is put that on hold while the fleet becomes operational. You could have one year without many missions

to the space station and let it be manned by Russian. vehicles," said Mr Caceres.

RUSSIA

Concern for Soyuz missions

By Andrew Jack in Moscow

The Russian Buran ("snowstorm") space shuttle, which bears a remarkable resemblance to its US counterpart, sits today

almost forgotten in Gorky Park, a central Moscow amusement park.

Abandoned for reasons of cost after a successful unmanned flight in 1988, it bears witness to the end of the prestige-driven

cold war space race between the US and Soviet Union, and the start of a more hard-nosed commercial battle, in which Russia

seems often to have held the upper hand.

In the past decade, it has not only persuaded the, US to provide it with substantial assistance in participating in

an international scientific space programme. It has also capitalised on its expertise to create a highly lucrative export

industry.

Using tried and tested technology - notably in the form of the Proton cargo rocket - Russia has generated substantial income

from commercial satellite launches, albeit with a foreign market restricted for a long time by US-imposed quotas

and more recently by the downturn in demand from the telecoms sector.

Similarly, its long-established Soyuz manned capsule has a strong record that has allowed it to maintain regular dockings

with the Mir and adapt easily to the ISS, to which it has transported three foreigners - including two "space tourists" - in

the past two years. That has allowed it to maintain the record for longevity of space flights and boast an impressive safety

record, with the last fatal accident in 1971.

"Some of the infrastructure may be crumbling, but a lot of the development costs were already written off under Stalin,"

says Brian Harvey, a Dublin-based space expert and author. "The development costs of the [US] shuttle were less than anticipated,

but its ongoing maintenance costs have been much higher."

While the shuttle's greater cargo- and passenger- carrying capacity (up to seven astronauts compared with Soyuz's three)

has allowed the US to put more people into space, Russia could easily make up the difference at a lower cost by increasing

the frequency of Soyuz and Proton flights to the ISS.

Nevertheless, alongside the strong personal solidarity that members of the Russian space programme were expressing this weekend

for their US colleagues, there was also concern that the Columbia accident could throw their own future work into doubt.

Russia has maintained commercial and military space programmes. But, in the scientific sphere, since US pressure to abandon its

Mir space station, its limited resources have all been concentrated in international partnership with the ISS.

It could gain through substitution, if the US permitted a shift to the greater use of Russian cargo and passenger transport.

But it could also suffer if US financial and political commitment to the entire programme waned in the coming months.

EUROPE

Accident recalls failure of Ariene

By Victor Mallet in Paris

"Really, in space, you never have enough margin." Professor Wolfgang Koschel, a German space engineer, could easily have

been referring to the technical failures that seem to have caused the disintegration of the US space shuttle Columbia.

In fact Prof Koschel was talking - last month about another space industry disaster, albeit one with no human victims.

He was announcing the findings of an inquiry into the failure of an enhanced version of Europe's Ariane 5 rocket on its maiden

flight in December.

Like the older US and Russian space programmes, Europe's modest ambitions for unmanned space exploration and satellite

launches have been marred by occasional, but spectacular, explosions and equipment failures. The latest one has prompted

soul-searching among scientists and governments about the future of the European space programme.

Prof Koschel's inquiry concluded that the upgraded version of the Ariane 5 veered off course -prompting its destruction

by remote control along with $600m (E557m) worth of satellites - probably because the engine's newly designed exhaust nozzle

broke up as a result of intense heat and pressure.

In spacecraft and launcher design, where weight at launch is all-important, there were always difficult compromises

to be made between weight and strength. It seemed, he said, that the tubes cooling the Ariane 5's new nozzle were

not strong enough and there had been no way on the ground to test the rocket motor at full power in a vacuum.

INTERNATIONAL SPACE PROGRAMMES

China will go forward with schedule for manned fight

By Victor Mallet in Paris

China has vowed to press on with its ambitious space programme, which includes plans to become as early as this year

the third country to send an astronaut into orbit, writes Richard McGregor in Shanghai.

President Jiang Zemin sent an official message of condolence to George W. Bush, his US counterpart, yesterday for the disaster.

But a leading Chinese scientist, Chen Maozhang, was quoted by the Xinhua official news agency as saying that the

accident would not deter China from pursuing its own space plans.

Started in 1992 and conducted in great secrecy ever since, China's space programme has recently been allowed a higher

public profile. There are plans for a manned flight this year.

The manned programme received a confidence boost last month with the successful landing of the Shenzhou-IV spacecraft

in Inner Mongolia after a week-long flight.

In an interview last week, Zhang Qingwei, president of the China Astronautics Technology Group, said the return of

the spacecraft showed "the reliability and safety of the spacecraft have completely reached the standards for manned flight."

He added: "Implementation of the manned space flight project has made China the third country in the world to master

manned space flight technology, has further increased China's influence, and has created favourable conditions for China to

exploit and peacefully use space resources."

Mr Zhang's comments underscore how the success of the space programme has been elevated into a matter of national prestige

for China, as well as a potential battleground for the possible exploitation of natural resources.

Following the US accident, proceeding with a manned flight is also now a significant test of nerve for the country's leaders

and its scientists.

On top of the manned space flight, China has plans for the launch of nine domestic satellites this year.

India

India yesterday went into mourning for Kalpana Chawla, the 42-year-old scientist who died on board the Columbia shuttle.

As the first Indian in space on an earlier Nasa mission in 1997, Ms Chawla, who was born and educated in the state of Punjab,

was feted as a national heroine, writes Edward Luce in Bangalore.

Last month she was pictured on the cover of India Today, the country's leading weekly news magazine, to celebrate the

achievements of overseas Indians.

"For us in India, the fact that one of them was an India-born woman adds a special poignancy to the tragedy," said

Atal Behari Vajpayee, India's prime minister, in a letter of condolence to Mr Bush yesterday.

The Columbia tragedy has also focused attention on India's own space programme, which - with China's - is considered

to be the most advanced in the developing world. But officials point out that unlike most other space programmes,

India has chosen to forgo manned space missions.

"We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the moon or the planets,"

said Vikram Sarabhai, the father of India's space programme when it was inaugurated in the 1960s.

Instead, India is considered a world leader in "satellites for development" - or remote sensing technology which collect

high-resolution data designed to help economic progress. It has seven such satellites in orbit.

India also has four meteorological satellites that are considered world leaders in providing specialist data that can help

predict natural disasters such as cyclones, landslides and flash floods.

But there is also friction with the US over the development of India's space programme, which New Delhi insists has been developed

with indigenous technology and is not for military use.

Japan

Japan's space programme is likely to be severely affected by the break-up of the Columbia, a senior Japanese official said

yesterday, writes David Pilling in Tokyo.

"There will be grave effects from this," said Koji Yamamoto, executive director of the National Space Development Agency (Nasda),

yesterday.

Japan had been due to send its fifth astronaut into space next month, when Soichi Noguchi was expected to take part in

a space shuttle flight on the Atlantis mission. Officials said yesterday this mission would inevitably be postponed,

possibly for a lengthy period.

In addition, Tomiji Sugawa, another official involved in Japan's space programme, said the Columbia accident would affect

Japan's plan to build a module on the International Space Station. That was because US space shuttles were the main means

of transporting astronauts to the station, he said.

Nasda is also expected to launch a total of eight H-IIA rockets by 2005, with launch operations due to be transferred

to the private sector after that. Japan's first spy satellites were also expected to be launched from the Tanegashima

Space Centre in Kagoshima Prefecture next month.

Japan took the decision to deploy spy satellites in 1998 after it failed to foresee the launch of a North Korean missile over

its territory.

Financial Times February 3 2003.

DEATH OF A DREAM

After Columbia: if maned space flight is to continue, Nasa will need to rethink its

strategy and finances

If serious flaws are found in the Columbia shuttle, the International Space Station

may have to be abandoned despite substantial investment, writes Clive Cookson

The Columbia disaster leaves the US with a stark choice in its position as global leader in manned space flight: either phase

out human activities in space or make a huge investment in a reinvigorated, safer programme.

The loss of the Challenger shuttle in 1986 was even more of a shock than last Saturday's tragedy, because it was the first

time a manned spacecraft had been lost in flight. The television pictures of Challenger's explosion soon after lift-off

from Cape Canaveral were more spectacularly awful than the distant views of Columbia disintegrating 60,000 metres up in

the Texan skies.

But the US government and Nasa, its space agency, were able essentially to return to business as usual after Challenger.

There was an intensive safety review, the three remaining shuttles were grounded and altered and a new one (Endeavour) was built

for $2bn. Flights resumed in 1988 after a gap of 2 1/2 years.

This time it will be much harder to resume normal operations. For a start, there are no spare parts and production facilities

left to build a new shuttle, as there were 17 years ago, and to tool up again from scratch to build a 1970s-designed

spacecraft would be an absurd waste of billions of dollars.

So Nasa will be left at best with a fleet of three operational shuttles, assuming that the coming safety reviews do not find

a fudamental flaw in the spacecraft that would make it impossible for any of them to fly again. Even if the cause of Saturday's

tragedy turns out to be something specific that can be corrected relkatively easily, it has raised fears about the general

risk of using shuttles to lift people into orbit hundreds of kilometres above Earth - particulary when they are manageg by

an organisation that for years has been criticised for being demoralised and underfunded. Although manned space flight is

intrinsically and the men and womem who volunteer for astronaut training are well aware of the dangers, the death of

two shuttle crews in 113 flights goes beyond what most safety experts would see as an acceptable risk. Over the years Nasa

officials have talked privately about expected catastrophic loses ranging from one in 100 to one in 250 shuttle missions.

But the most important new ingredient in the equation is the International Space Station, the manned orbital laboratory being

built by a US-led consortium at an estimated cost of $60bn. Aithough Columbia's ill-fated final flight was a self-contained

scientific mission, this was an exception. The shuttle fleet's main role these days is to carry astronauts and materials

up to the ISS.

Construction of the space station was to have reached peak intensity this year and next, with 10 shuttle flights scheduled

to carry vital components into orbit. Russia's rocket-launched Soyuz craft can ferry people between Earth and ISS and unmanned

Progress rockets will continue to supply the crew with food, fuel and other consumable items. The Russians launched such

a cargo flight yesterday. But there is no substitute for the shuttle's heavy-lift ability.

The space station cannot grow at all while the, shuttle fleet is grounded and, even if the three surviving shuttles can

resume flights, it seems certain that the construction programme will fall far behind the current target of completion by 2006.

Nasa and its international partners will need first to decide when to remove the three current ISS residents, Ken Bowersox,

Don Pettit and Nikolai Budarin. They have been in space since November and were due to be replaced by a fresh crew on board

the shuttle Atlantis next month. All are in good health and could safely stay in space until June. If necessary, they can

return home in the Soyuz emergency capsule attached to the space station.

The next question will be whether to keep the space station manned by crews who will essentially just be doing maintenance

work and perhaps a few scientific experiments, until construction can resume; or whether to leave it unoccupied apart from

occasional visits by Russian spacecraft to keep it in the correct orbit.

"I think Nasa would be very reluctant to 'mothball' the ISS without a crew because it would deteriorate and could be difficult

and expensive to reoccupy," says Peter Bond, space science adviser to Britain's Royal Astronomical Society. Sergei Gorbunov, a

spokesman for the cash-strapped Russian Space Agency, agrees. "Without cosmonauts regularly working there we could lose

control of such a big station," he says. Soyuz and Progress could keep the ISS manned in the absence of shuttle flights,

though it would need financial help to build additional spacecraft. "It takes two years to build a Soyuz, not to mention

the gigantic financial investment."

But in the worst event - serious structural flaws being discovered in the whole shuttle fleet, making it unsafe for the craft

ever to fly again - the ISS might have to be abandoned. "The situation would have to be really drastic before that decision

was made," says Mr Bond, "because it is already half built, many billions of dollars have been spent and 16 nations have made

hardware that is waiting on the ground to go up to the space station."

President George W. Bush's first reaction to the loss of Columbia was to commit the US to continue manned space flight. But

this may require a complete rethink of Nasa and the financial resources committed to it. In real terms the space agency's budget

has been in decline since the Apollo moon landings finished in 1972. Many senior staff today are tired veterans. They boast

a record of many years' distinguished service to the space programme but do not have the enthusiastic energy of the scientists

and engineers who built Nasa in the 1960s.

The Bush administration's current financial plans envisage a decline in funding for human space flight from $7.1bn in 2001

and $6.8bn in 2002 to $5.8bn in 2006. Fiscal stringency has been accompanied by chronic indecision about whether and how to

replace the ageing shuttle fleet.

Before Saturday's tragedy Nasa had hoped to keep the shuttles flying until 2015. Lockheed's proposed X-33 shuttle replacement

project was scrapped for technical and financial reasons in 2001and the space agency's latest idea is to develop a Orbital Space

Plane for use from 2010. This would be a small and highly manoeuvrable vehicle, launched on top of a conventional rocket

and capable of rescuing people from the space station in an emergency - but would not have the capacity to replace the

shuttle directly.

Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 17 astronaut and space analyst, told space.com: "I suspect this tragedy will add new impetus

to the Orbital Space Plane, more than likely changing its direction to become not just a rescue vehicle but also a vehicle

for access to space."

But what, ultimately, is the point of manned space flight? Scientific exploration of the solar system and beyond can be done

far more cheaply with robotic spacecraft - and indeed Nasa has a spectacular record of unmanned planetary missions such as the

Viking Martian lander in the 1970s, the Voyager explorations of Jupiter and Saturn in the 1980s and the Mars Pathfinder rover

in the 1990s.

If gaining scientific knowledge were the only goal, no one would send people into space as unmanned missions offer so much more

value for money, says Lord Sainsbury, UK minister for science and space. For this reason, Britain has resisted the blandish

ments of its partners in the European Space Agency to play any role in the International Space Station, let alone plans

to build manned space vehicles.

The real motivation for manned space flight is the human colonising instinct and love of adventure, combined with national

security concerns. These came together in the 1960s when US politicians invoked "manifest destiny", a phrase originally

used in the 1840s to justify American expansion westwards to the Pacific Ocean. They saw it as mankind's destiny to move beyond

Earth, first to the moon (under US leadership) and then through the solar system and eventually the whole galaxy. At the same

time, cold war concerns provided a powerful spur to beat the Soviet Union to the moon.

Although manned space flight stopped being a true adventure after the Apollo moon landings, because subsequent missions have

not gone beyond orbit around Earth, Nasa staff have retained a belief that their work is ultimately aimed at human colonisation

of space. Sean O'Keefe, the new Nasa administrator installed by Mr Bush with a budget-cutting mandate, made clear last year

that he subscribed to that view; his vision for the agency is to "improve life here, extend life there and find life beyond".

Even after 30 years of technical disappointment and financial restraint, Nasa still employs visionaries to develop futuristic

propulsion systems, investigate the biology of interplanetary travel and plan manned flights to Mars and beyond.

National security is less of a reason to send Americans into orbit than it was when the Soviet Union had a flourishing

independent space programme but it has not disappeared. Indeed it seems unlikely that the US would withdraw from manned

space flight just as China claims to be on the threshold of becoming the third country to send its own astronauts into orbit,

possibly within the next year.

Initial political reactions to the Columbia disaster suggest Mr Bush will have widespread support if he decides to expand

the manned space programme and start serious development of a safer successor to the shuttle. "We can't step back," Senator

Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas told Fox television. "We wouldn't be the greatest country on earth if we did. This is the time

to say we are not going to continue cutting [Nasa's] budget." Senator Bill Nelson of Florida, a former astronaut, agreed:

"We've got to fulfil our destiny as a character of people as explorers and adventurers and go to Mars."

Indeed, it is just possible that Mr Bush could later this year officially proclaim a manned mission to Mars as a long-term US

goal in space, in an effort to restore morale and renew Nasa's mandate. The deaths of seven astronauts could yet give birth

to a new human adventure.

80 experiments: more PR than science?

"There is enormous public appeal of having humans do the science," Nasa once said in defence of manned space flights.

Thus the seven Columbia astronauts were not only brave explorers. They also acted as researchers in space.

Billed as a "scientific" flight, the ill-fated Columbia mission performed more than 80 experiments. But as the world mourns

the loss of the crew, Nasa must come to terms with a harsh reality: human participation in these experiments was largely

unnecessary.

Aside from assessments of the effect of space flight on the astronauts themselves, the vast majority of micro-gravity

experiments can be and often are - conducted remotely, using robotics controlled by computers at Nasa's control centre.

One challenge for Nasa, in fact, has been finding ways to involve astronauts more intimately in the experimentation

process. The agency was installing "glove boxes" on the International Space Station to allow astronauts to manipulate

materials within a sealed chamber. Traditional scientific tools such as beakers and test tubes are useless in the micro-gravity

environment of space. Conducting even the simplest experiments by hand can be perilous. A single escaped drop of water can play

havoc with a spacecraft's instruments.

But Nasa believes scientific experiments are valuable for public relations purposes. One of the most symbolic conducted

on the Columbia involved collaboration between a Palestinian biology student and an Israeli medical student. Another test

was to discover the specific scent produced by a rose and an Asian rice flower in space. The astronauts were also observing

the way flames burn in micro-gravity.

Critics charge that Nasa's space experiments are of doubtful scientific benefit. Similar tests are performed on Earth,

at far lower cost, in "bio-reactors" that simulate a micro-gravity environment. In space, astronauts have observed that

frogs have trouble jumping in micro-gravity and somersault instead. Birds have a hard time taking flight. Plant roots

grow every which way. And it once took a spider several days to learn to spin a web in the low-gravity environment.

Some believe the knowledge gained from these experiments does not justify their cost. "They do experiments in space

like 'Do jellyfish swim in the same way in zero gravity?"' Robert Parks of the American Physical Society said before

the Columbia tragedy. "No space-based research has ever had any impact on science whatsoever."

Nasa defends its tests. "There are many aspects of space we can't mimic on Earth," Nasa's Dr John Charles said at the

Columbia launch. "We can turn down air pressure in laboratory vacuum chambers and bombard samples with space-like radiation. We

can't turn off gravity, though, or look down on Earth from above."

The space agency hoped to ease funding crisis by renting out space laboratories. On the Columbia, half of the experiments

were for commercial purposes. Yet Nasa has not been able to charge much for the laboratory property. Commercial contributions to

the programme have remained static at about $50m for the past few years.

But space exploration advocates see the mission as preparation for a manned flight to Mars, long a US space agency dream.

Until this weekend, manned missions to Mars and beyond were considered the agency's best hope for reviving the glory days of the

1960s, when space budgets were fat and the public was wildly enthusiastic. As the world digests the implications of the Columbia

disaster, the human and financial cost of those ambitions is likely to be reconsidered.

Victoria Griffith

The loss of the shuttle Columbia has thrown the future of manned space flight into question as the world, waits

to discover whether the US will scale back its efforts or renew its commitment to space exploration.

The loss of the shuttle Columbia has thrown the future of manned space flight into question as the world, waits

to discover whether the US will scale back its efforts or renew its commitment to space exploration.

"There is enormous public appeal of having humans do the science," Nasa once said in defence of manned space flights.

Thus the seven Columbia astronauts were not only brave explorers. They also acted as researchers in space.

"There is enormous public appeal of having humans do the science," Nasa once said in defence of manned space flights.

Thus the seven Columbia astronauts were not only brave explorers. They also acted as researchers in space.